Federal Reserve officials are due to issue new economic projections on Wednesday, with GDP growth likely to be a blow-out number that sets the stage for an historic experiment by U.S. central bank policymakers.

Fed Chair Jerome Powell and his colleagues are betting the economy can take off from the COVID-19 pandemic without generating excessive inflation, and have vowed to keep interest rates at rock-bottom levels and a spigot of money flowing for an extended period as they lean into a potential economic boom in a way not seen since the early 1970s.

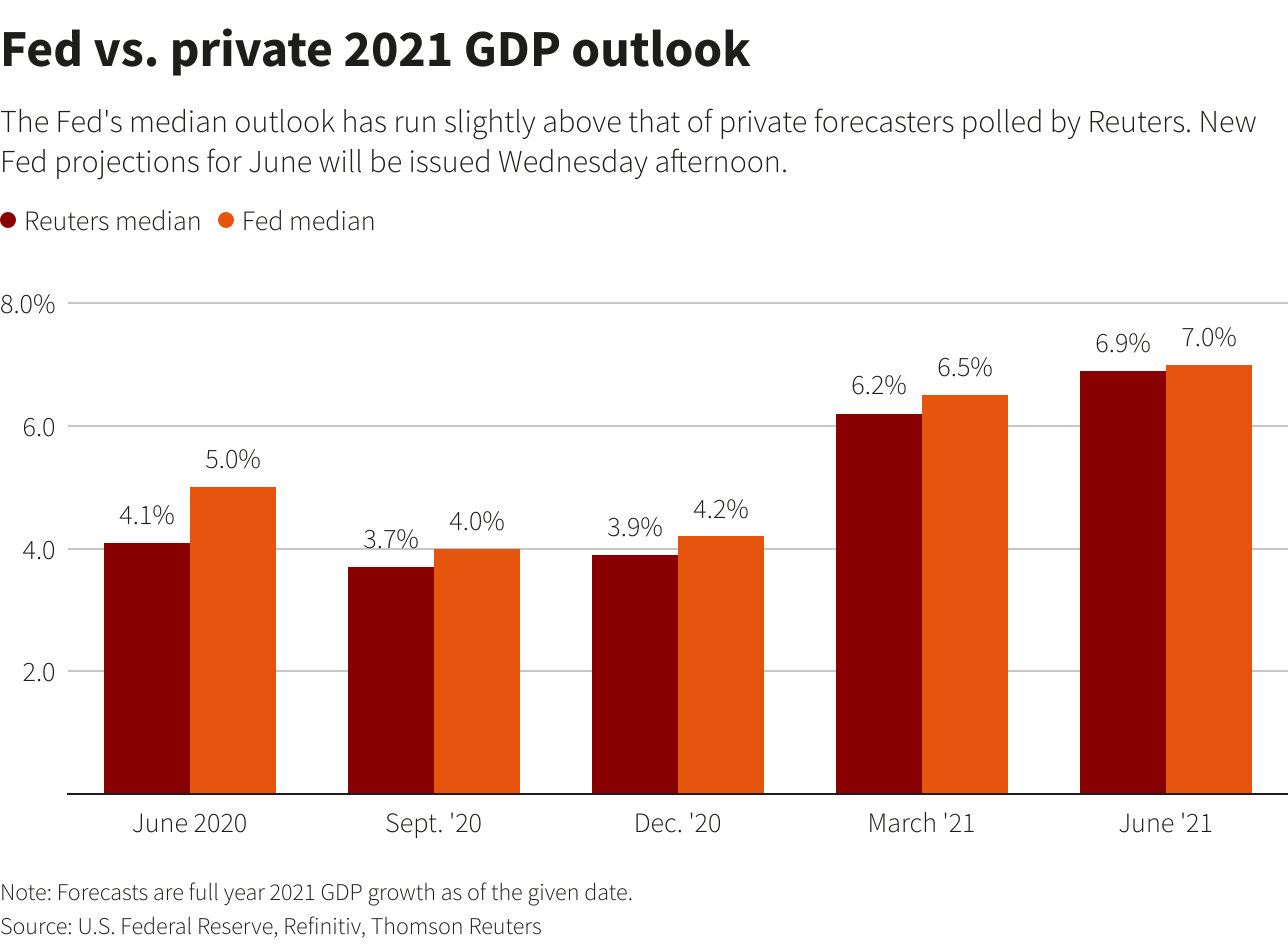

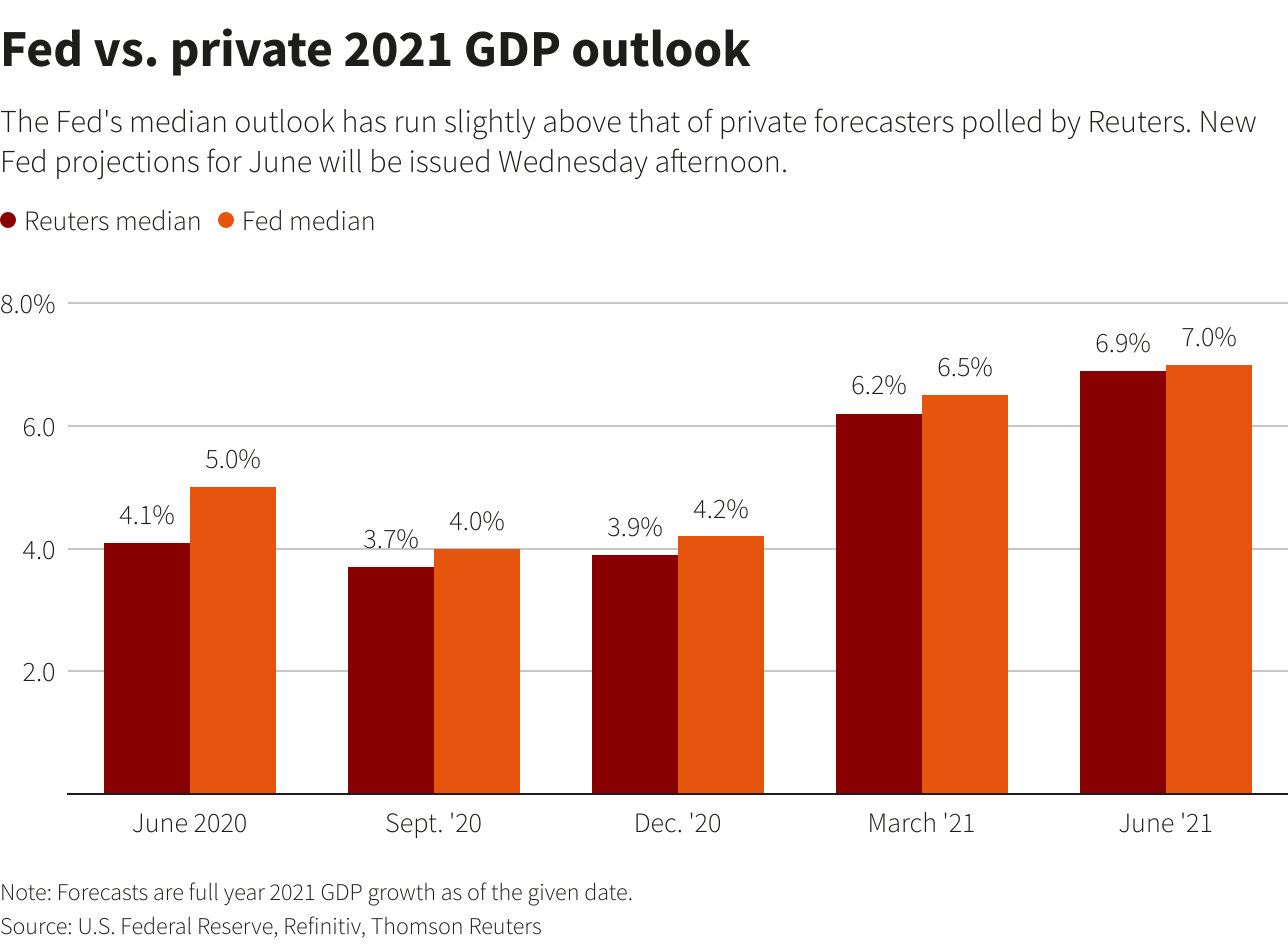

In each of the quarterly forecasts released since June, the median GDP growth projection of Fed officials has been slightly above the median of private forecasters polled by Reuters. If that holds, it would translate into expected growth this year of more than 6.2% - the highest annual rate in 37 years.

But when they issue their policy statement at the end of a two-day meeting on Wednesday, Fed officials are expected to restate what they’ve promised for months now: to keep the central bank’s benchmark overnight interest rate near zero and cash flowing into the economy until Americans are back to work, trusting that inflation will remain contained, as it has been for about 30 years.

The economic projections and policy statement are scheduled to be released at 2 p.m. EDT (1800 GMT). Powell will hold a news conference shortly after, an event that could prove tricky for the Fed chief.

Markets predict the Fed may be forced to act sooner than expected.

Some policymakers could even hint at that if new projections show more of them anticipate a rate increase sometime in 2023, rather than a year or more later.

If a majority see a 2023 hike, “Powell will have his work cut out for him” explaining how that meshes with a promise to get the economy back to full employment before reducing the crisis support rolled out when the pandemic struck, Tim Duy, chief U.S. economist for SGH Macro Advisors, wrote this week.

Still, investors are already betting on earlier hikes, and some economists are also raising a red flag along with their forecasts. Morgan Stanley, among the more bullish in predicting the economy will have fully escaped its pandemic hole by September, sees the Fed’s approach producing a “hotter but shorter” business cycle that is likely to prompt it to tighten monetary policy early next year.

Benchmark U.S. Treasury yields hit a fresh 13-month high and U.S. stocks were trading largely lower on Wednesday as investors awaited the outcome of the Fed meeting.

The coming cycle would be less like the last three expansions - the one ended by the pandemic lasted a decade - and more like the period after World War Two when the intervals between recessions were shorter and intervening growth stronger.

That epoch ended when then-President Richard Nixon encouraged loose monetary policy ahead of his 1972 re-election. Arthur Burns, who was the Fed chief at the time, kept interest rates low as the economy accelerated, and is often blamed for the ensuing rampant inflation that dogged the country for a decade.

This time is different, Fed officials argue. Indeed, Powell’s legacy may hinge on whether inflation remains tame as the economy recovers, or whether prices spike, forcing the central bank to pull back its support - perhaps with millions of Americans still out of work.

Their arguments are well-rehearsed. Inflation and unemployment don’t behave as they used to; lower levels of joblessness can now coexist with low inflation.

The Fed made substantial changes to its policy statement last year encompassing that thinking, and the guidance issued in December is expected to hold for now. It pledged to continue its monthly $120 billion of bond purchases until there was “substantial further progress” towards full employment and 2% inflation. Moreover, it said interest rates would not increase until those goals were actually met.

None of those things have happened yet, a point Powell has stressed recently and will likely again on Wednesday. The economy remains about 9 million jobs short of its pre-pandemic level; the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation, at 1.5%, is well short of its goal; a new index of slow-moving inflation expectations is also below target.

‘CLEAR-EYED’

Still, it is a pivotal moment as Fed officials issue forecasts incorporating a bounty of new information.

Since their December projections, more than 100 million COVID-19 vaccines have been administered in the United States and daily deaths due to the virus have fallen by two-thirds. Optimism has spiked, and states have begun lifting restrictions on businesses and reopening schools. Washington also has approved two new relief packages worth about $2.8 trillion, money now rolling into household and business bank accounts.

Much has changed since the Burns era, when wages and inflation were tightly linked, the economy relied more on manufacturing and imported oil, and unforeseen shocks from an oil embargo were just ahead. [Related graphic:

here]

The Fed’s new approach, moreover, isn’t an in-the-moment response to political pressure, but a policy shift meant to reflect changes in the economy officials spent years studying.

With an emphasis on job creation and downplaying inflation, the new framework seemed well suited for the job market crisis spawned by the pandemic. The issue now is how it meshes with an economy that may recover faster than thought possible.

Analysts at BlackRock have praised the Fed for being “clear-eyed” about the economy’s problems during the pandemic and in its response to it.

But, wrote Rick Rieder, BlackRock’s chief investment officer of global fixed income, “at some point, the financial stability risks that emanate from an extremely low policy rate, coupled with the real economy boom that we expect, could in fact force the Fed’s hand.”